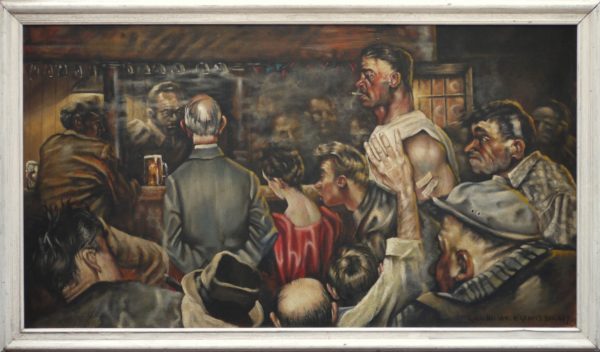

Nelson, George Laurence (American 1887-1978)

Nelson was born George Laurence Hirschberg in New Rochelle, NY, on September 26, 1887, the son of Carl and Alice Kerr-Nelson Hirschberg, and the youngest of three brothers. His parents were artists of no little repute on both sides of the American and European scene. His father, Carl Hirschberg, born in Berlin, Germany, came to the United States where he started school in New York City at the age of six. Before he finished his education, he became one of the prime movers and shakers in the American Art movement, first as reorganizer of the Art Students League and then as co-founder of the Salmagundi Club in 1875. As a young man, he went to Paris to study, and there met and married another young artist, from London, named Alice Kerr– Nelson. She was the daughter of George William Kerr– Nelson, Lord of Chaddleworth Manor in Northcutt, Middlesex England, and was descended from Elizabeth Kerr, England’s most noted painter of flowers, an artist who startled England with an art exhibit in London in 1763, daring to become a professional artist in a man’s world. Laurence’s mother, often referred to in American circles as THE Woman of the Century, was the one person who had the greatest influence upon him.

It was into this background of artists, rich in history, talented in artistic ability, that Laurence was born. By the age of four he was drawing animals, and at five sketching portraits, generally of his mother. In 1897 when he was ten, as a vehicle for his drawing and writing, Laurence began a magazine, written in pencil on tablet paper, first calling it The American Monthly Paper, changed to The American Weekly Paper as the issues became more numerous, and then to The Weekly Duet when his brother Edgar joined as assistant editor.

By this time the family had moved to Buffalo and there Laurence attended local schools, being an editor of the high school review. In 1904 his crayon sketch of a cow won first prize, a pair of skates, still at Seven Hearths, in a contest sponsored by Crayola Crayons. It would be the first in a legion of awards and prizes that he would gather during the long years ahead. After graduation, he returned to New York City to enter the Art Students League to begin his formal study of art. In 1906 he exhibited his work, using the name George Laurence Nelson to avoid confusion with the work of his well known parents.

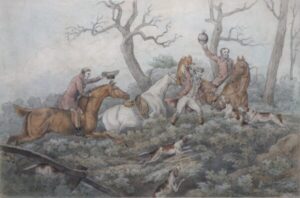

On May 27, 1911, he sailed on the S.S. Minnehaha for London; he would remain in Europe—France, Spain, Italy—for two years, studying under Laurens, Gerome and Constance at the Beaux Arts and Academe Julian. His reputation grew quickly. Before leaving for Europe he had been commissioned by Mrs. Henry Clay Frick to copy twenty paintings in the Metropolitan Museum for her home, now known as the Frick Museum. She and her friends sat for him for portraits and by the time he left for Europe he was an international acclaim. Hence it was not strange that he received, aboard the Minnehaha, a cable from England’s King George V: “Have heard of your departure for London...I need a new set of ancestors painted...there are sixty -four of them...will you do the job for ten guineas...half cash, bal in six months...or five percent off for cash...signed George, Buckingham Palace.” The cable had been sent collect, costing the twenty-four year old Nelson $40, a fact which he never forgot. But he did the paintings, before leaving for Paris, staying at the Delmonico Hotel during the commission—all at his own expense!

He spent his time well in Europe, going to museums where he copied famous Masters, studying technique, colour and design. He loved the region of Normandy best, and he spent much of his time in the area about Douarnenez, as his father had before him. But because of the illness of his mother, he ended his foreign studies, returning to the United States in 1913, shortly before her death. He established his studio first at 15 W 67th Street, and then at 33 on the same street, remaining there until he and his father moved to Good Hill and then to Seven Hearths, in Kent, CT, where they began their summer school for painting (room and board being twenty-five cents per week).

Late in 1915 a young critic from the New York Globe, a leading fashion model of New York society, came to his studio for an interview for a feature article on his work. Her name was Helen Carlotta Redgrave. But instead of her doing an interview with him, Laurence painted her portrait, a profile of one whom he called the most beautiful girl in the world. Judging from the painting, she was indeed all that he claimed. On August 21, 1916, they were married, and for fifty-six years Helen and Laurence complemented one another in writing and painting, in ink and in pigment, in theatre and opera, flowers and people, city and country, spending themselves, doting on their daughter Bunny and their grandchild Bonny.

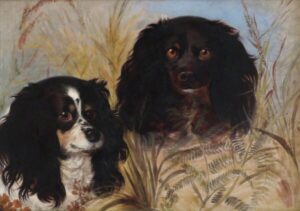

Perhaps the secret behind Laurence Nelson was his mother, Alice Hirschberg. C. Y. Turner and William Merritt Chase claimed that she was America’s greatest woman artist and a woman truly liberated—a master of painting in oil and water colour, etching and wood engraving, designer of fashion, magazine illustrator, collaborator with Turner and Chase in some of their greatest works. George Laurence Nelson came by his talent from a rich heritage, but he was who he was because his mother taught him how to live, how to dream, how to draw and encouraged his love for art and music (he played five instruments and had a rich voice).

Second to her were his mentors James Whistler and John Sargent. They taught him through their writings and paintings how to work with tools, how to reverence the brush and its stroke, how to see life as it is meant to be lived, how to share a vision however delicate with others. That he learned well from them is evident in the very early painting he did of his mother, a work often attributed to Sargent.

The likes of George Laurence Nelson is not likely again, at least not in numbers. His dry humor, quick step, long stride, shy smile, twinkling eye, warm handshake, effervescent conversation, enthusiasm for the new, deep humility when faced with praise, amazement when sought after for interview or one of his works—all these and more spell out this resident of Seven Hearths, who so loved this spot of history that he left it so others might share in its beauty and significance. He knew his origins, appreciated his many talents, knew well his life’s mission, and he could and did take pride in what he accomplished, whether it might be a gold medal, a comment from his peer, an international recognition. His was a gentleness fashioned and tempered by the three loves of his life: his mother, his wife, his “mistress” art. He has taken his place in American history as one of the ten greatest portrait painters and one of the all time lithographers, but he has taken his place in Kent and its history, not because of his international stature or reputation in American Art; rather because he chose to live here, share himself as a warm genuine human person who knew how to love and be loved, and finally to be buried in the land he loved so well—Kent.

Kent, nestled along the banks of the Housatonic, established itself as a community in 1739. The character of this quaint town with its distinct architecture and history have become home to many artists and writers.

The Seven Hearths home, built in 1751 by John Beebe Jr., was given to the Kent Historical Society in 1978 by artist George Laurence Nelson, proprietor of the dwelling since 1919. Now the Historical Society’s headquarters, its furnishings portray the various stages in Kent’s history. The home is also listed on the National Register of Historical Places.

This biography is excerpted from the book, New Life for Old Timber: published by the Kent Historical Society 1982.